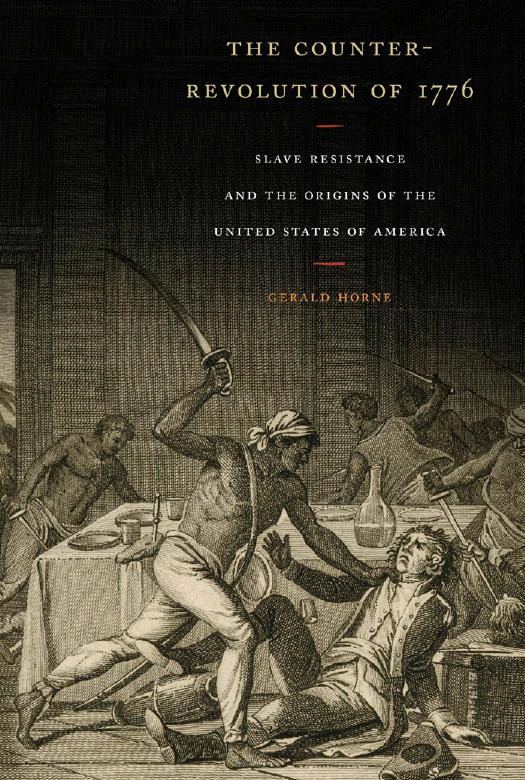

The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America by Gerald Horne

Author:Gerald Horne [Horne, Gerald]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Tags: History, United States, Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), Social Science, Ethnic Studies, African American Studies, Discrimination & Race Relations, Slavery

ISBN: 9781479893409

Google: cMAUCgAAQBAJ

Amazon: 1479893404

Publisher: NYU Press

Published: 2014-04-18T04:00:00+00:00

The upshot of the 1756–1763 war was to provide an energy boost for the slave system—which is why there was so much anger on the mainland about London’s decision to limit the slave trade to Cuba during its brief rule. Compared to the island, by the 1770s heavy importations to the mainland meant the market for the enslaved there was (in a sense) glutted.54 This suggested that a bounteous profit could have been made by exporting Africans from the mainland to the island.

Thus, shortly after the war ended, a London bureaucrat noticed that “the number of Negroes is constantly increasing in America,” particularly since there was “more care in breeding them than is taken in the West Indies.” Their number had doubled in recent years in Rhode Island, while those in New York had grown to about fourteen thousand and Pennsylvania’s was reaching toward twenty thousand. This bureaucrat concluded that if their growing number was taxed, it would both decrease their growth and encourage the deployment of more European servants.55 But bureaucratic blather about limiting the number of mainland Africans had been spilling forth for years with little visible impact, which suggested that the Crown was not in touch with reality.

Hence, despite this bureaucratic admonition, by the early 1770s Africans were flooding into the mainland, particularly to Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia. Part of this trend was a rush to acquire the enslaved in response to the non-importation agreements targeting London: that is, mainland rebels disgusted with London not least because of taxes imposed to pay for the costs of the 1756 war had moved to curb trade with the British isles (which had the not accidental impact of strengthening mainland merchants and weakening metropolitan competitors). Naturally, after Madrid was ousted from Florida, imports of Africans gyrated upward—since flight southward was curbed—which should have conciliated those colonists upset with the Cuban limitations.56 But this too brought complication since this peninsular province was close to the Bahamas, and there were mostly “Blacks” and “Mulattoes,” it was reported in 1768, who possessed a “very bold and daring spirit which makes it necessary to have a proper force,” that is, a “Garrison as soon as possible.”57 The 19th century would reveal that the Bahamas presented a threat to mainland slavery just as Spanish Florida had earlier.58

For ineluctably, those Bahamians with arms would include Africans, complicating the existence of slavery there and in Florida. And since Cuba was back in Spanish hands, the opportunity was re-ignited for Havana to resume its noisome meddling in the internal affairs of British colonies. Africans were continuing to flee from British soil—now the Bahamas—to Havana, which, said a leading official, was “very detrimental to His Majesty’s subjects here whose property chiefly consists of their slaves,” a practice worsened by Cuba’s claim that sanctuary was provided “under the ridiculous pretense of their becoming Catholic.”59 Those who had fled, he said, were “engaged in turtling” and had managed to get within “ten leagues distance” from Cuba.60 Thus, by 1769, the

Download

The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America by Gerald Horne.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7678)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5409)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5398)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4552)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(4367)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4355)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4233)

Captivate by Vanessa Van Edwards(3828)

Mummy Knew by Lisa James(3670)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3524)

The Worm at the Core by Sheldon Solomon(3469)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3450)

The 48 laws of power by Robert Greene & Joost Elffers(3203)

Suicide: A Study in Sociology by Emile Durkheim(3002)

The Slow Fix: Solve Problems, Work Smarter, and Live Better In a World Addicted to Speed by Carl Honore(2990)

The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell(2896)

Humans of New York by Brandon Stanton(2860)

Handbook of Forensic Sociology and Psychology by Stephen J. Morewitz & Mark L. Goldstein(2689)

The Happy Hooker by Xaviera Hollander(2678)